Foreign language knowledge level and usefulness

The more someone knows a foreign language, the more useful that knowledge is. This doesn’t imply though that the knowledge and usefulness are proportional. In this post, I argue that they are not proportional.

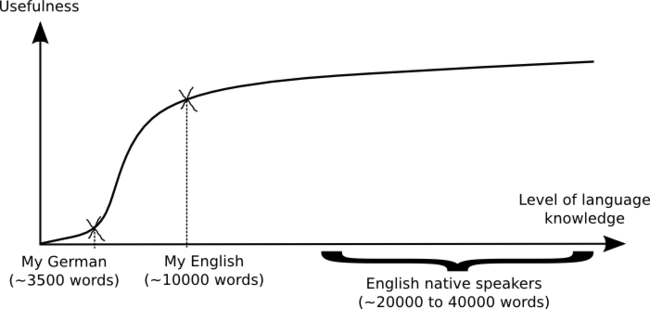

In my view, the usefulness of a language as a function of the knowledge level actually looks like this:

Knowledge level and effort #

First we need to map knowledge levels into numbers. Let’s define knowledge level as something proportional to the minimal learning effort. This means that if a knowledge level requires a person to spend at least X amount of effort, and another level requires the same person to spend at least Y amount of effort, the ratio of the numeric values of the knowledge levels should be the same as the ratio of the minimum efforts required by them, i.e. X/Y.

There is actually a very concrete metric which satisfies this requirement: the vocabulary size of a person. So we can say that my English knowledge level is around 10000, because I know around 10000 English words. My German knowledge level is around 3500, because I know around 3500 German words. If I want my German knowledge to double, I have to put in the same amount of effort that I have put in so far.

Usefulness #

First of all, by usefulness I don’t mean how much someone can profit from knowing a language. Instead I mean how well someone can use the language when there is such an opportunity. (To clarify further, someone might say that “English is more useful than German because it is spoken by more people and it is the de facto common language of science and engineering”. But according to my use of the word “usefulness”, both English and German native speakers have an almost maximum “usefulness” in their own native language.)

So we need a numeric metric for the usefulness of a language knowledge level. Let’s say that if you can use the language well (without a dictionary, etc.) in X percent of the situations when the people you are communicating with use that language (including reading, writing, listening, speaking), then the usefulness of your language knowledge is X.

Back to the graph #

The graph nicely shows the following learning curve: In the beginning, you need to learn a lot for a language to be at least a little useful in real life. Then as you learn more, the language becomes more and more useful, until you can speak it fluently. At that point, you are still far away from native speakers, but increasing your knowledge will once again increase the usefulness very slowly.

To take my example, my knowledge level of English (10000 words) is roughly 3 times my knowledge level of German (3500 words). But my English level is much more than 3 times as useful as my German level. (This was the initial observation that led me to the graph.) This is how I experience these two knowledge levels:

- To understand a book in German, I need a dictionary (and a lot of time to look up stuff in that dictionary). To understand a movie in German, I need the script or subtitles, a dictionary (+ a lot of time) and a “pause” button. Reading emails is better (I can understand most things in them without a dictionary). Writing emails also requires a dictionary (+time). So while my current German level is not totally useless, it is almost useless.

- My English knowledge level is totally different: I can do almost anything in English that I can do in my native language (which is Hungarian). Granted, I don’t know the names of many things in English, but I rarely need these words.

Conclusion #

My personal conclusion is that I should focus on studying German:

- I should not focus on English, because the effort of learning let’s say 4000 words will hugely improve the usefulness of my German, while it would have a considerably smaller impact on the usefulness of my English.

- I should not start learning a new foreign language either, because after learning let’s say 4000 words, I will just have another almost useless language knowledge, instead of having a useful German with 3500+4000=7500 words.

A related observation is that if the knowledge level is after that steep portion of the graph, it is much easier to maintain the knowledge, because you will enjoy books, movies, etc. in that language. This also supports that I should focus on German.

Notes #

- I measured the size of my English vocabulary with testyourvocab.com and vocabularysize.com. It is difficult to define what a word is, so I went with the numbers provided by these websites.

- I have been using the ExponWords web application (disclaimer: I’m the developer of ExponWords) to practice all German words I’m supposed to know; so to check the size of my German vocabulary, I just need to check the number of my German words there.

- I’m not saying that vocabulary size is the only thing that determines a person’s knowledge level. What I’m saying is that it is sensible to define the knowledge level as proportional to the effort put in to learn a language, and that the vocabulary size is proportional to the effort. And since the vocabulary size of a person in a language is a single number, this can be used as an indicator or knowledge level. Grammatical knowledge, the ability to parse and understand the spoken text in real time, and the ability to construct spoken text in real time are just as important.

- I’m not saying that it takes the same effort for different people to get to the same knowledge level. But my assumption is that if e.g. level A requires 100 hours effort from a person, and level B requires 200 hours, then every person has to spend twice as much effort to reach level B than to reach level A. I also assume that this proportionality holds if different people use different learning techniques: if person 1 needs 100 hours of class for level A and 200 hours of class for level B, and person 2 needs 1 months living abroad to reach level A, then person 2 will need 2 months living abroad to reach level B. So effort can mean “number of words”, “hours of active learning”, “months living abroad” – according to my assumption, these are interchangeable.

- I’m also not talking about the joy or pain of the effort. Once you know a language well enough, putting in further effort is usually more fun (because you can talk to people, read books, browse websites, listen to audiobooks, radio and podcasts, watch movies, etc. instead of talking only to teachers, reading only textbooks, listening only to the audio track of the textbooks).